Natural Transformations: Why are Natural Transformations Natural?

I am a member of Colorado State's Applied category theorey seminar, and every semester we talk about the basic definitions in category theory. I have been trying to become a better mathematician, trying to better understand not the "what" but the "why". In this particular seminar I have put a lot of though into categories without objects. I wont talk about that too much here but it may affect my language. Anyway I have been thinking a lot about naturality, as it is supposedly(maybe controversially) the primary objective of category theory.

My new found understanding of natural is partially motivated by algebra and some of the forgotten definitions there, such as inner homomorphisms. Never the less I think the notion of inner gives a very informative foundation for what it means to be natural.

When is a Functor Inner? and what does that even mean?

For some motivation lets look at the term "Inner" in the context of groups to get some motivation for why we might want a similar term in the world of categories.

A group automorphism $\varphi:G\rightarrow G$ is called an inner automorphism if $\varphi(g)=x^{-1}gx$ for some fixed element $x\in G$. Inner automorphisms are the automorphisms that are really coming from conjugation. A Group $G$ can act on its self by conjugation, and for each element the actions by elements give us the inner automorphisms. These are very special automorphisms because they come from within the group. In a sense the group already knew about these particular automorphisms. Furthermore conjugation in groups often looks like relabeling. For example consider the permutation $(1,5)(2,4,7,8)$ conjugated by $(1,2,3,4)$, which would be $$(1,2,3,4)^{-1}\cdot(1,5)(2,4,7,8)\cdot(1,2,3,4)=(1,7,8,3)(2,5)=(2,5)(3,1,7,8)$$ We can see that the structure hasn't changed drasticly but we have relabeled $1,2,3$ and $4$

These are really the key idea behind the term "Inner", they refer to things that are coming from within the algebraic object you are studying, and dont change the underlying structure is a significant way. So how does this apply to functors? We lets look at some diagrams and try to deduce what inner could possible mean.

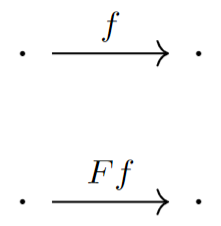

Consider a functor $F:C\rightarrow C$ that maps a morphism $f$ to the morphism $Ff$

To call this functor inner, it should have more or less the same idea as in the case of groups. Where the morphism $f\in C$ is related to morphism $Ff\in C$ by some sort of "conjugation". And this conjugation should more or less behave like a relabeling, and should affect the underlying structure in a significant way. But we have to be a bit more careful here as what ever we choose to do will depend on the sources and targets of the morphism $f$, as they determine when we can and cant compose with $f$. So we may want to enforce that the functor maps morphism according to other morphisms already in the category $C$. Lets add in objects to help contextualize what is going one here.

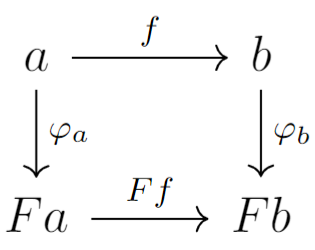

Our functor $F$ is a mapping a morphism $f:a\rightarrow b$ to the morephims $Ff:Fa\rightarrow Fb$ but now we will enforce that for the object $a$ and $b$, the sources and targets of $f$, that there are morphisms $\varphi_a:a\rightarrow Fa$ and $\varphi_b:b\rightarrow Fb$ that create the following commuting square

algebraically this is telling us about a commuting $\varphi_b \circ f = Ff \circ \varphi_a$. In a sense this is telling us that the morphism $f$ is equivalent to the morphism $Ff$ up to some morphisms applied to the source and target, and we can think about this as being similar to just relabeling the sources and targets. Infact if $\varphi_a$ was invertible this would give us an explicit conjugation $\varphi_b \circ f \circ \varphi_a^{-1}= Ff$.

So now we can define what inner will mean in the context of categories. An \textbf{inner endofunctor} is a functor $F: C \rightarrow C$ along with a collection of maps $\{\varphi_a | a\text{ an object of }C\}$ for each object(each source and target) such that for every morphism $f:a\rightarrow b$ we have

Again this is really telling us that the morphisms $f$ and $Ff$ agree is some way internal to the category, by other morphism of the category.

Maybe in a future post I will give an object free definition. But i may just skip to adjoint functor which is where i believe the object free definition are nicer.

is a natural transformation? and what makes it natural?

This notion of inner can be used to define an important idea in categories, that of the notion of natural. What does it mean for a map to be natural? or as we will see soon, what does it mean for a family of maps to be natural? First it is important to recognize that what it means to be natural should and will depend on the greater context of the maps you're looking at. If you want a group homomorphism to be called natural you better have a definition that does so in that context, the context of group homomorphisms. This immediately points towards categories as a possible way of doing this, and maybe suggests that what ever we end up doing should also be internal (or "Inner") to the context or the category.

It is almost important to note that this notation of natural, that we are about to define, is primarily used in the context of objects. I may later comment on how it applies to object free categories but often a different starting point is taken. That is to say I will unfortunately go against my belief that categories don't need objects and use the objects. But historically that is how natural transformations came into existence.

To call a map natural, it should exist broadly. A single morphism between isolated objects is definitely not natural. This suggests that a map being natural should require that it exists, in some way, for all objects, hence natural maps should really be a collection of maps. For example we often want to make claims like "Every group is naturally isomorphic to its opposite group" or "the determinant is a natural map". Lets consider the determinant example to build a bit more intuition. For this to be natural we first need to determine the context in which it exists. Often the determinant is thought of as a group homomorphism between the groups of invertible matrices $GL_n(R)$ over some ring $R$ and the ring of units $R^*$. So our context will be the category of group homomorphisms. This is a bit tricky as the determinant isnt a map defined for all the objects in the category of group homomorphisms. But the object we care about (the groups $GL_n(R)$ and $R^*$) are special, they come from the images of Functors, the functors $GL_n(-)$ and $(-)^*$. This suggests that natural transformations need not be a collection of morphisms for all objects but should be a collection of morphisms for all objects coming from some special functors (or equivalently the should be parameterized by the domain of the functors). In this example the determinant is going to be a natural transformation, meaning it will be a collection of maps defined on each matrix group $GL_n(R)$ or equivalently the underlying commutative ring, as each commutative rings gives us the matrix group through the functor $\det = \{\det_R:GL_n(R)\rightarrow R^* | R\text{ a commutative ring}\}$ This is why many authors will define a natural transformation as a morphism between functors, in this case its its between the functors $GL_n(-)$ and $(-)^*$ as these parameterize the sources and targets of our collection of maps.

So lets get to a definition!

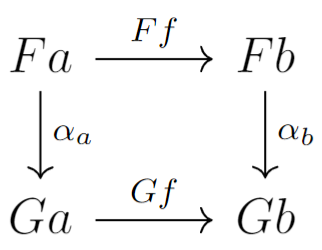

Let $F,G:C\rightarrow D$ be two functors, then a natural transformations $\alpha$ is a collection of maps $\alpha=\{\alpha_a:Fa\rightarrow Gb | a\text{ an object of }C\}$ That defines a functor $A:F(C)\rightarrow G(C)$ on the images of the the functors mapping $Ff$ to $Gf$, that is also inner with respect to $\alpha$, meaning we have the following commuting square for every morphism $f\in C$

All this goes to say that a natural transformation can be though of as a functor on the images of the functors $F$ and $G$, that is also "Inner" in the greater category in which the images live.